打印这篇文章

打印这篇文章

(Excerpt from “The United States Joins The New Silk Road: A Hamiltonian Vision for an Economic Renaissance”)

The ancient Silk Road linked two great centers of civilization—Asia and Europe—uniting the landmass of Eurasia into a single continent and opening the interior of this continent to human settlement and a cross-fertilization of culture. The New Silk Road, which is already in the process of being built, promises to far supersede the historic accomplishments of its namesake. It is integrating Eurasia through modern modes of high-speed transport and other types of development, but can also be extended on a global scale.

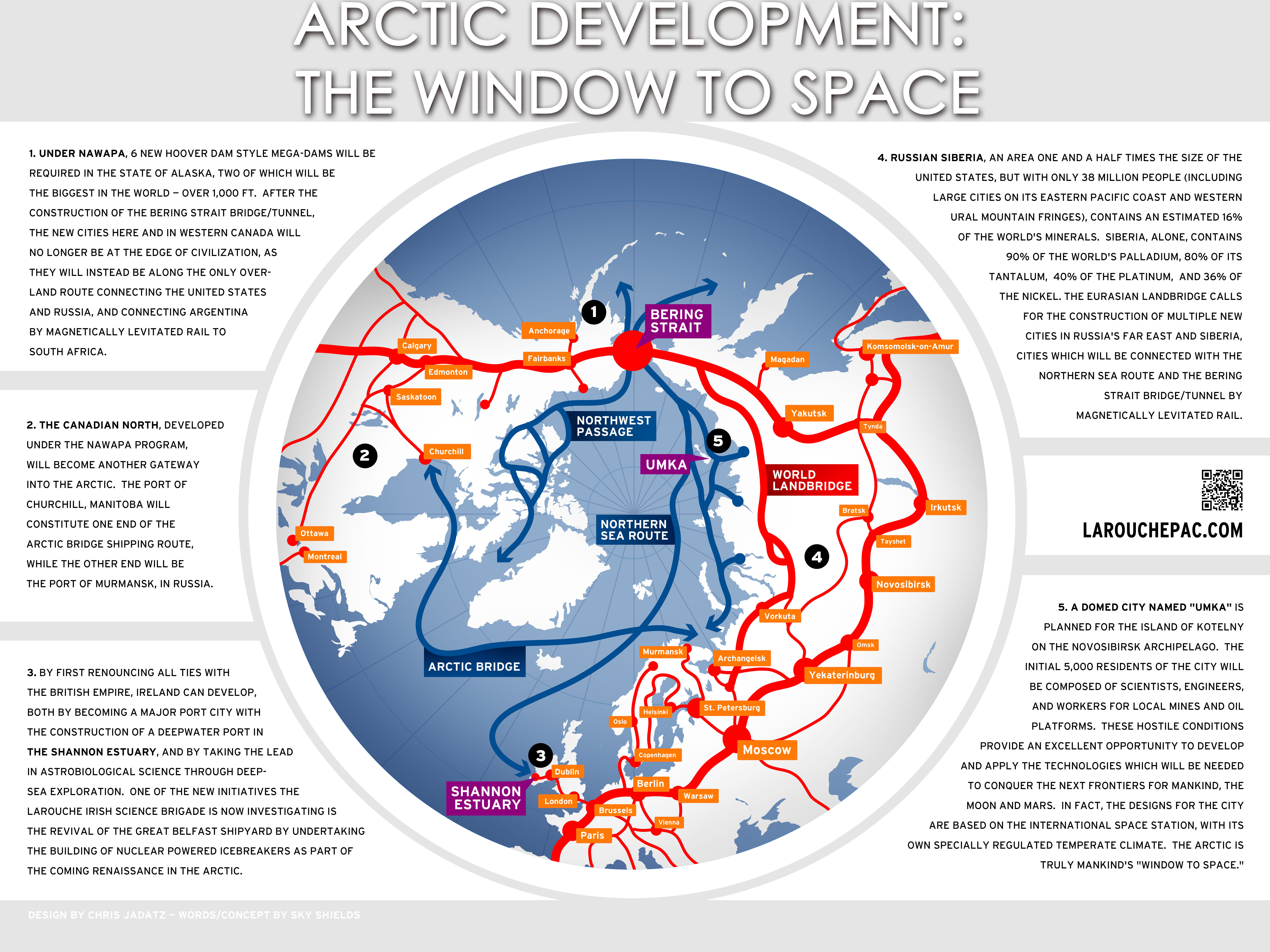

The New Silk Road can become the World Land-Bridge by means of the construction of a Bering Strait rail connection, uniting the two great landmasses of the planet, Eurasia and the Americas, just as the original Silk Road bridged the East and West. Imagine boarding a magnetically-levitated train in downtown Paris or Berlin, travelling at 250 mph across the steppes of Siberia, through an underwater Bering Strait tunnel across more than 50 miles of ocean, emerging on the other side in Alaska, and ultimately arriving in New York City!

Not only would the completion of the Bering Strait rail connection connect these two great landmasses and place them in direct economic, cultural, and commercial communication with each other, but it would definitively shift the center of global civilization away from the trans-Atlantic and towards the Pacific basin, as well as opening up the Arctic, mankind’s modern-day frontier, to human exploration and development.

Overcoming the engineering challenges involved in bridging the gap between Alaska and Siberia would represent a feat of human accomplishment. By means of 55 miles of tunnels under the Bering Strait, the transportation systems of Eurasia and the Americas could be linked, allowing the development of two of the most neglected regions of the planet. Some 2,000 miles of new railway in Eurasia and more than 600 miles in North America will need to be built, under rugged northern conditions on both continents, to complete the connection with the transport systems which already exist.

This vital transportation corridor would be more than merely a means to get from point A to point B; it will open up vast potential for mineral and raw materials development in the Far North. It is not merely a high-speed replacement for shipping across the Pacific; it is an opportunity to develop this severely underdeveloped region of the U.S., Canada, and Russia, allowing its fallow riches to benefit the people of the planet, including through the development of new cities and research centers in this region, unlocking a new opportunity for human discovery and endeavor.

LaRouche’s movement has campaigned for a Bering Strait connection since the 1970s. This project served as a critical link in a global chain of development projects envisioned by the LaRouche movement at the time, to be the foundation of a new international economic order and financed through investments by the International Development Bank and related institutions of international credit. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990, Lyndon and Helga LaRouche’s vision of a Productive Triangle to integrate the economies of Western and Eastern Europe was expanded to become the Eurasian LandBridge, spanning the entirety of the Eurasian territory.

The LaRouche movement campaigned vigorously to bring this perspective of mutually beneficial development to the governments of every major country on the planet, as the foundation for a new strategic order of peace through progress, as opposed to a perpetuation of geopolitical war.

During the 1990s, a number of critical studies were commissioned to explore the possibility of extending this Eurasian Land-Bridge idea to encompass the Bering Strait connection, bridging into the Americas, including most notably a 1995 visionary over-view study co-authored by American engineer Hal B.H. Cooper, Jr. and Professor Sergei A. Bykadorov of the Siberian State Academy of Transport in Novosibirsk. In the recent decade, additional plans for this project have received renewed interest.

An April 2007 conference convened by Russia’s Council for the Study of Productive Forces titled “Megaprojects of Russia’s East: A Transcontinental Eurasia-America Transport Link via the Bering Strait” called for detailed feasibility studies of the project. The conference was addressed by numerous leading Russian academicians, as well as by the former Governor of Alaska, Walter Hickel, who delivered a speech titled “A Transcontinental Eurasia-American Transport Link via the Bering Strait: Megaprojects as the Alternative to War” in which he called the Bering Strait connection “a project that may change the world, a project of joining creative energies, replacing missile defense systems with a territory of international cooperation.”

The conference was also addressed by Lyndon LaRouche in the form of a paper which was presented to the gathering titled “The World’s Political Map Changes: Mendeleyev Would Have Agreed” in which LaRouche stated:

“The development of a great network of modern successors to old forms of rail transport, must be spread across con-tinental Eurasia, and across the Bering Strait into the Americas: the economically efficient development of presently barren and otherwise forbidding regions in entry into the urgently needed future development of the planet as a whole… To this end, the tundras and deserts of our planet must be conquered by the forces of science-driven technological development of the increased productive powers of labor. Development must now proceed from the Arctic rim, southwards, toward Antarctica. The bridging of the Bering Strait becomes, thus now, the navel of a new birth of a new world economy. ”

The design for the Bering Strait connection which was produced by this conference won a Grand Prize at the World Expo–2010 in Shanghai, China. In May 2014, Prof. Wang Mengshu of the Chinese Academy of Engineering stated that China and Russia were discussing its implementation.

However, the idea of bridging the Bering Strait is not a new one—it is an idea which has captured imaginations for over 150 years. Even before Russia sold Alaska to the United States in 1867, there was support in the U.S. Congress for a telegraph line across the Bering Strait to Russia, which had been a key U.S. ally against the British during the Civil War. And later, in 1890, as Russia was initiating the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway modeled on the Transcontinental Railroad of Abraham Lincoln, Governor William Gilpin of the Colorado Territory promoted a “grand scheme of a Cosmopolitan railway,” reaching “north and west across the Strait of Bering; and across Siberia, to connect with the railways of Europe and all of the world.”

While Russia and China are reviving discussions of completing this long overdue project, the United States has yet to reciprocate and take the neccesary steps to turn this great vision into a reality.