打印这篇文章

打印这篇文章

This article is an edited and abridged version of June 17 weekly ‘New Paradigm for Mankind’ show on LaRouche PAC TV. The speaker/author is Megan Beets.

Two days ago Lyndon LaRouche lead a discussion which centered on the following question: Since the collapsing trans-Atlantic system means doom for civilization, where is a future for civilization to come from? We do see the Win-Win policy being promoted by Xi Jinping, and being adopted by the BRICS nations, but the discussion centered around the principle which is at the core of the solution: the necessity of bringing about within human society a coherence of mankind, uniting all the different expressions of mankind throughout the world around a commonality of principle and a commonality of a mission. To set the tone for my presentation, I will read a couple of quotes from LaRouche from that discussion;

“You have to bring about something which we’ve lost in the United States. You have to build a certain kind of harmony, a human harmony where people of different talents become part of a common chorus, and the idea of the parts, the unity of the parts, the cooperation of the parts of the common chorus is the principle of a republican nation. And that’s the way you want to organize people to organize society. What you have to do is to bring a consonance, a symphony of consonance together of people where all are more or less converging on a common understanding of each other which is a correct one. So if you take classical musical composition and performance you have an ideal model for developing the minds of people. And the idea of the chorus is the unifying of a whole population to a common sense of reality and mission, whatever their other skills are, and they rejoice.”

In another passage which is extremely relevant for my presentation today, he said;

“The idea is having the true idea of harmony which resides in something which is a characteristic feature of the human mind. The human mind is prepared only to function with a concept of harmony. And the idea of harmony as harmony in the form of classical song — choral work — is the model for all harmony in mankind and everything in life that is harmonious. The machine tool, everything around that you are playing with, is all a part of harmony, and if you don’t have harmony, then you have disjunction and you have degeneration. It’s that simple. But the point is the principle by name is very simple, it’s called Classical artistic composition. Music. Music is the medium for typifying Classical harmonic composition.”

The concept of harmony expressed by Mr. LaRouche — a harmony among peoples, a principle of unifying very different people, with very different roles in society, from very different cultural and national backgrounds, upon a common principle — is very different from the idea that dominates politics today in the United States: popular opinion. Harmony is not berating people to cohere or conform with a popular opinion, but instead to bring people to a discovery of a higher uniting principle, which is precisely what we are seeing in the process unfolding with the BRICS today. Expressed thus, the principle of harmony is not only a musical principle. It is something much more universal which goes directly, at its roots, to the discoveries of Johannes Kepler.

The tuning of the universe

Our idea today of harmonics — both of modern harmonics as they are used in music, and as expressed by Mr. LaRouche — is rooted in the work of Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), who discovered the Solar System, and through that discovery established the modern form of well-tempered harmonics, as it is used in classical music today. This began with Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), who picked up on Kepler’s ideas very directly. I am not going to go through a full elaboration of Kepler’s discovery here, but will say a few things to set up the idea.

Kepler dumped all previously existing assumptions about what the Solar System is, about the nature of astronomy itself. He discovered the Solar System as a physical system. The way that Kepler did that, in brief, is by conceiving of all of the motions of each planet as an expression of the one mover — the Sun. Kepler imagined each planet as a member of an orchestra, playing a musical tone in a musical piece which is conducted by the Sun. A member of an orchestra is not an independently acting individual, which just happens to be in the same room as other independently acting musicians. There is a commonality of mission among members of the orchestra to play the same musical piece, and to play together in harmony, to express the intention of the composer, and also of the conductor who is conducting them.

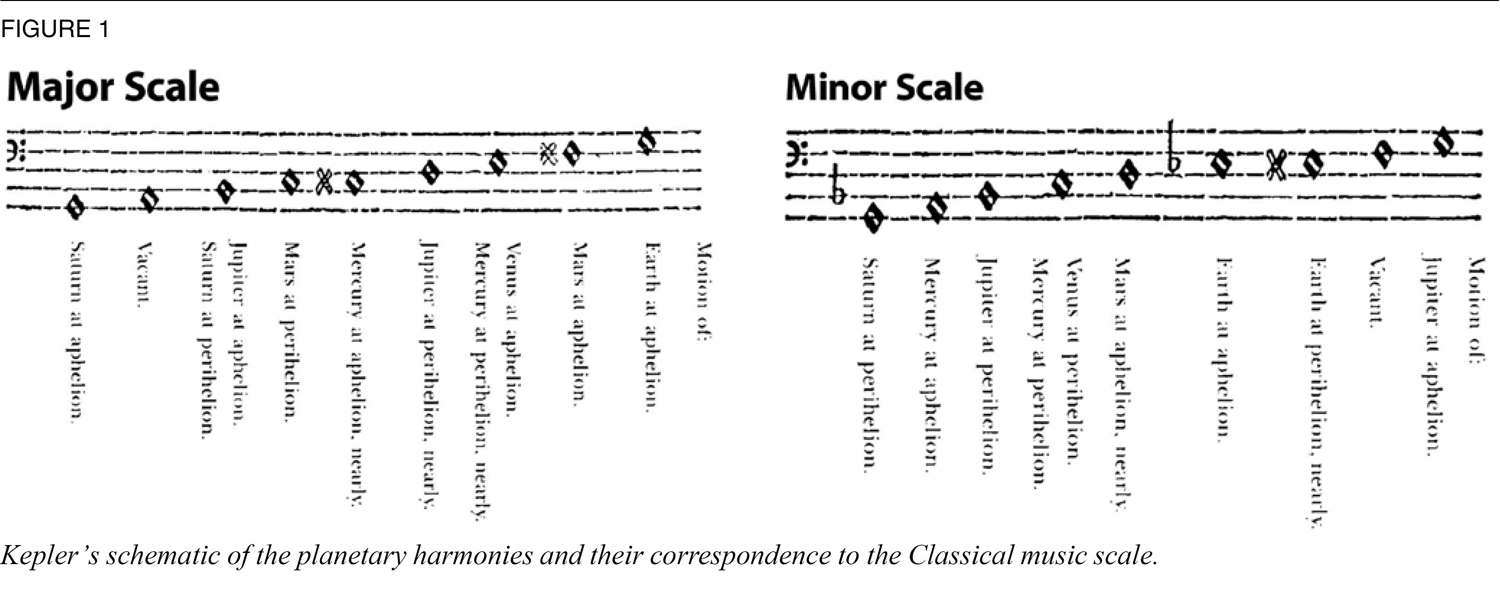

You see in FIGURE 1 that Kepler demonstrated that the fastest and slowest motions of the planets in the Solar System cohere to the tones of a major scale and also a minor scale, as we have it in music today. As in music, the tuning of these planetary scales is not a one-by-one relationship with the Sun. Instead, each of the planets’ motions is modulated so that each is as harmonious with all of the others as possible. The result is not a simple idea of tuning, but a much more complex, changeable, varied idea of tuning, as also expressed in highly developed human music: classical string quartets, orchestras, and so forth. For Kepler there was no separation between the physical process which he imagined (and then discovered to be true) in the Solar System, and the principles of human music (which only later came to be expressed in the most developed Classical music).

This brings us to the real issue at heart with music. As you see with Mr. LaRouche’s idea of harmony, and with the way in which Kepler dealt with harmony in the Solar System, the basis of music is not sound. That might be a strange idea for many people. How is it that music is not sound? When you go to a concert hall to hear a concert, aren’t you hearing sound? When you rehearse a piece of music, when you sing, aren’t you producing sounds? Yes, sound is involved. Sound is a certain result which is involved in the process of performance, but the music is not actually sound. It is not built from sound. The combination of sounds does not make music. At this point, I want to read another quote from Mr. LaRouche, from a discussion he led last month:

“The music lies not in the music. It lies in the motive of the music. Otherwise, what does the music mean? It’s just a form of noise making. You don’t want to make noise. You want to capture the mind of people, not their ears. And the result should come through the mind, not through the ears. You interpret the thing not as it’s heard — the heard sounds. What you should hear is the brilliant music of the unheard performance. You don’t have to hear it because you are already captured by it. Your mind is an instrument. Your body and your soul are an instrument of music. It’s not the music that makes that. It’s the body and the soul which makes that. The music is incidental.”

I think that this is a completely different idea of music than almost everybody has today, certainly in the United States and Europe. It flies in the face of what people accept and tolerate as popular notions of music: sound, entertainment, self-expression. What Mr. LaRouche is getting at is that there is a substance to music which goes far beyond the notes. It goes to the capacity of the human mind to have new insights and discoveries about the nature of man itself, and to be able to convey and communicate these conceptions to other human beings. The mode of communication which we tend to call Classical music can be clothed in sound, and will be expressed in sound, but the motivation is soundless — a higher passion of mankind.

This notion of music is the basis of the Classical tradition that Western Civilization was founded upon, and resonates also very strongly with the notions of music and art found in the writings of Confucius. Having established that idea as the standard of art, I would like to discuss a very important specific issue relating to how art is performed today, which bears strongly on the possibility (or impossibility) of continuing the performance and composition of Classical music into the future. The issue is that of tuning.

Why Classical musicians today are out of tune

It is a fact today that almost every single Classical musician on the planet today, be they professional or amateur, sings or plays out of tune. Out of tune in the sense that they are singing or playing at the wrong pitch.

What is meant by that: singing at the wrong pitch? When one goes to a concert hall to hear a concert, before the performance begins, the musicians tune their instruments. There is a standard pitch which is played, which all the musicians tune their instruments to. This also happens if one goes to a piano concert, or a singing concert with a piano accompanying, and the piano strings must be tuned. No matter what the performance, there is a standard pitch which is chosen, and all the notes are tuned to conform to that pitch. In most cases today, the standard pitch which is chosen to determine the tuning pitch of all the instruments, which also determines the pitch at which singers sing their songs, is too high, and arbitrarily so. In some cases it is much, much higher than it should be, meaning that every note that is sounded is a little bit or a lot higher than is natural.

Perhaps this sounds like an issue for music specialists or concert aficionados, but this is not an academic issue, or one for debate solely within the “music world,” having no consequence for politics or general daily life. This is an intensely political fight, and it is one which was waged more than a hundred years ago by Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901), the great opera composer, who was also a senator in the first parliament of Italy. This fight was re-initiated by Lyndon LaRouche in the 1980s and continues up to today.

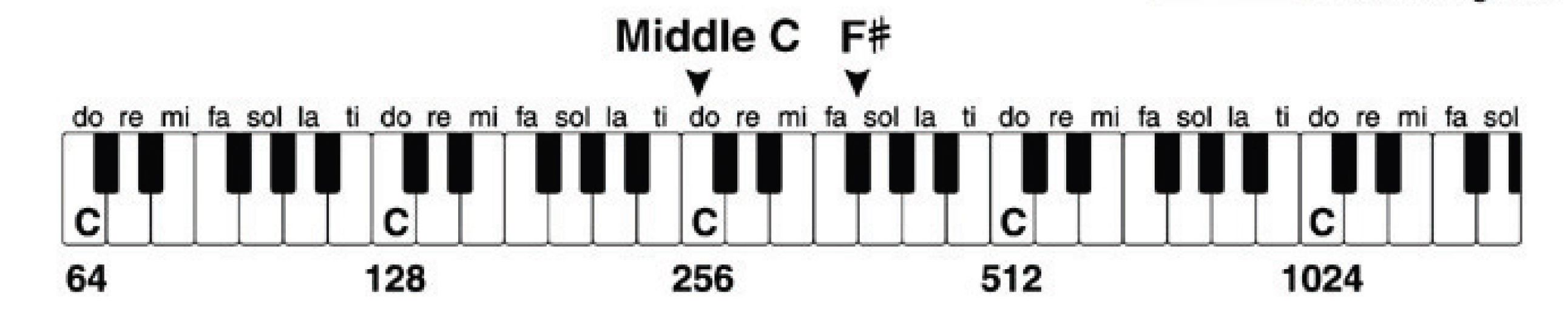

First, why is this a political fight? And why can we say that there is such a thing as a right or a wrong pitch? How can one say that an orchestra is tuned wrong? Who has the authority to say that? Nature. Nature has the authority to say that. The human voice has the authority to say what pitch it wants to sing at — how it works best. All music today, be it vocal music, instrumental music, or piano music, is based on the human voice and the characteristics of expression of music based in human poetry. Specifically, it goes to characteristics of the voice as trained according to discovered principles of how the human voice actually works, as developed from the Renaissance. The human voice operates best when it is singing at a particular pitch. It does not operate well when it is stretched to sing at a higher pitch, or even a much lower pitch. The pitch which was agreed upon by the best classical musicians of the 19th Century and some beyond in the 20th Century is a pitch where middle C is tuned to 256 vibrations per second. That is, the correct pitch of that note is 256 vibrations per second; if it were more (e.g. 260), the note would sound a little bit higher in pitch to you, and if it were less (e.g. 246) it would sound a little bit lower. This proper natural pitch of C at 256 corresponds to the note above it of A at around 432 vibrations per second.

To those who do not play an instrument or sing, may not have an idea of what the differences in tuning sound like, so I will play a few examples for you. The first example is the tone A at the natural tuning of 432.

The second example is the same note, A, at the tuning which is adopted in many orchestras in the United States, A440. It is a little bit higher in pitch than A432. It’s a small difference, but it is a difference, and every note of the scale is adjusted up at least that much.

The third example is the same note, A, at 450, which is adopted in many orchestras around the world today. This difference, between A432 and A450, is much larger. It is almost a half step, the difference between two keys on a piano — two entirely different notes.

What is the result of doing this? First, the result on the singing voice. What’s the result for a trained opera singer who shows up in Vienna, for example, to sing an opera role, where the tuning is much higher than the natural tuning? Back in the 1980s and ’90s when the Schiller Institute ran an intense campaign to return the tuning to low tuning, we approached many of the top opera singers in the world on this issue, and all of them agreed: The high tuning damages the voices. It stretches the voices and makes the voices shift and change (in the way that they have to with the proper training) in the wrong place, and puts a strain on them. This can shorten the careers of singers, and also makes some of the music which was composed in the past at lower tunings un-singable. It can make some great music of the past unavailable to modern audiences, because we no longer have the voices around to sing that music, due to the strain of these arbitrarily high tunings.

The detrimental result is not just on voices — again this isn’t just an issue of the human voice. Incredible damage is done to many musical instruments, violins for example, when played at the high tunings. For a violin which was built to play at the lower tuning of A432, if all of the strings are tightened to meet the higher tuning, there is now more than 8 pounds of additional pressure on the body of the violin than there is at the lower tuning. Over time this causes tremendous damage to this great wealth of Stradivarius violins and all of the other wonderful instruments that have become part of human society, human culture.

The obvious question, given that the tuning varies so much from place to place (you never know what you’re going to get from one concert hall to the next), and that the higher tunings do so much damage to voices and instruments, is: who would want to do that? Who would want to do something unnatural? How did it get to be that way? Did people just forget what the natural tuning was and begin to choose whatever they wanted? No, that did not happen. The real fight around the nature of tuning is a fight over the nature of man, and over what music itself is. What is the purpose of music in society? What is the nature of the mind and the life of mankind? That’s what’s at the root of the fight around tuning.

The fight around tuning

Here follows brief sketch of some of the history of the fight over tuning pitch. As mentioned earlier, Verdi fought for legislation on this question in the 1880s, and LaRouche launched a campaign in 1986 to legislate the standardization of international tuning pitch at the low natural tuning of C256 or A432. However, the fight goes back much earlier. In the time of the Classical composers, Bach, Händel (1685-1759), Mozart (1756-1791), Haydn (1732-1809), there really was not a standardized pitch. One could travel from city to city, or from church to church within a city (most having an organ at a particular tuning), and the tuning pitch would vary widely. However, what is known is, that the tuning generally used by these composers was much, much lower than the modern pitches. For example, both Händel and Mozart used a pitch which was a little bit lower than A432.

The first attempt, which was more of an unofficial attempt, to standardize the tuning pitch came with the 1815 Congress of Vienna. The Congress of Vienna was the international conference held at the end of the Napoleonic wars to set up a new political structure of Europe. (Though what really happened at the Congress of Vienna was the re-imposition of fascism over Europe by the imperial powers.) At the Congress of Vienna the Czar of Russia gifted a set of musical instruments to the Austrian Military Band which were all at the new high tuning of A440. This was not just a whim on the part of the Czar of Russia; there was a political operation based out of the Congress of Vienna to control the culture of Europe, part of which was to begin imposing a new, higher pitch in music. The new band instruments had a much brighter sound and more dazzling sound (there are physical acoustical reasons for that), and this sound had much more physical impact on the listener. This set off a total craze of for the brighter sound, and beginning from this time, orchestras and bands across Europe began to raise the tuning of their instruments.

The London Philharmonic in 1820 tuned to A432. In 1842 they had gone up to A440 and by 1850 they were at A452. Something similar happened with the main orchestra in Paris, and many other cities. While people still played at the lower tuning, in general the pitches began to rise all across Europe, such that by 1877 at the Wagner Festival in London they were playing at A455, which is much more than a half step higher than the natural tuning. In New York City in 1880 the Steinway factory tuned their pianos to A457, which is extremely high. In reaction to this, there was a conference held in Paris in 1858 (largely due to the efforts of the composer Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868), who composed for the bel canto human voice) to standardize the pitch. The idea behind the conference was: The higher pitch is insane! We are losing our music, we are losing our voices, we must standardize to a lower pitch! The Paris conference officially adopted a standard of A435, which is very close to the low natural tuning, and which was the lowest pitch in use in France in those days. In 1881, in Italy, there was a Congress of Italian Musicians, largely inspired by what occurred in Paris, which officially called for Italy to adopt a similar standard in tuning of A432. This was supported by the composer Verdi, and after the resolution of the Congress of Italian Musicians, Verdi wrote a letter to the Italian government which reads as follows:

“Since France has adopted a standard pitch, I advise that the example should also be followed by us, and I formally request that the orchestras of various cities of Italy among them that of La Scala and Milan to lower the tuning fork to conform to the standard French one. If the musical commission instituted by our government believes for mathematical exigencies that we should reduce the 435 to 432, the difference is so small that I associate myself with it willingly. It would be an extremely grave error to adopt as proposed by Rome a standard pitch of A450. I also am of the opinion with you that the lowering of the tuning in no way takes away the sonority or the liveliness of the execution, but it gives on the contrary something more noble of a greater fullness and majesty than the shrieks of a too high tuning fork could give. For my part I would like a single tuning to be adopted in the whole musical world. The musical language is universal. Why then would the note which has the name A in Paris or Milan have to become a B flat in Rome?”

In 1884, three years later, the Italian government did officially adopt A432 as the standard tuning pitch for all orchestras of Italy. Similar motions were taken up in other countries such as Spain and Belgium. In 1885 there was an international conference in Vienna which turned out to be a huge fight. Verdi sent his friend Arrigo Boito (1842-1918), his librettist and close collaborator, as one of two Italian delegates, and instructed him to fight vigorously for 432 (or 435, as a compromise). While the Vienna conference was conflicted, the delegates did eventually resolve for A435. However, it never quite took hold in practice, and recognizing this, Verdi banned performances of his opera Othello if they were going to be at the high tuning. The point to be seen in these examples is that the issue of tuning was always a political fight.

Jump now to 1939, to the next major attempt to standardize the pitch internationally. This attempt was led straight from Nazi Germany by the Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels. From Goebbels came the request to London to please set up a conference to standardize the international tuning pitch at the same pitch then used by Radio Berlin: A440, the higher tuning. This London conference did demand a standardization at A440, at the request of the Third Reich, the the tumult and chaos of World War II however, prevented a universal implementation. There are more attempts made after World War II to standardize the pitch, which, for the most part, did begin to take hold. For example, in Vienna today the standard pitch is A444, and in Berlin it is A448, which is very high.

At this point, pause to consider what has been happening to music throughout this time (from the period of Bach and Mozart, through 1815, through the time of Verdi, and now up to World War II). What’s been happening to music throughout this time? There has been a great attack on Classical music, especially after the death of Johannes Brahms in 1897, and the idea of music as based in the senses – the sensuous effect of music – has been promoted. This came with the promotion of Richard Wagner (1813-1883), Richard Strauss (1864-1949), and Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971), whose best known work is The Rite of Spring, a musical portrayal of human sacrifice, all to create physiological sense effects in the human being, and to promote the idea that ugliness is music. That is what has been happening to music over the course of the parallel rise in the tuning. Obviously, this is completely contrary to the idea of music and harmony based in the powers of the human mind, of discovery, expressed by Mr. LaRouche.

LaRouche’s Fight for C256

Here is an overview what the LaRouche organization has done since 1986 to fight for restoration of the lower natural tuning, to save classical music and to save this precious power within society. In 1986 Lyndon LaRouche launched the campaign to save Classical music, calling for legislation to lower the tuning, which would be spearheaded by the Schiller Institute (founded in 1984 by Helga Zepp-LaRouche). By 1988 many of the top singers in the world had been contacted, a couple hundred of whom signed the Schiller Institute petition supporting such a call, and the Schiller Institute worked with two Senators in the Italian Parliament to introduce legislation in Italy in 1988 (100 years after Verdi) to lower the tuning pitch.

The Schiller Institute sponsored seminars with demonstrations of the difference in tuning of A432 and A440, and the more truthful expression of the music which is heard at the lower tuning, as opposed to the higher. Eventually, thousands of signers onto the petition, including Placido Domingo, Carlo Bergonzi, Piero Cappuccilli, Mirella Freni, Montserrat Caballé , and many, many others. Other signers were prominent singing teachers and instrumental musicians.

In 1988 in Milan, the Schiller Institute held the first seminar to demonstrate the importance of the lower tuning. The speakers included Helga Zepp-LaRouche, the chairwoman of the Schiller Institute seminar, world renowned baritone Piero Cappuccilli, the great soprano Renata Tebaldi, and other of the world’s most highly-regarded musicians. Interestingly, Tebaldi made the point in her remarks that the high tuning does not just affect the highest voices, sopranos or tenors, or singers who have to sing high notes; it is not about reaching high notes. It is about the natural placement of the voice. She said that even basses, altos and mezzo-sopranos who sing very low notes are adversely affected by this displacement of the natural order of the human voice.

There is a video available of demonstration at that conference by Cappuccilli. In the video, Cappuccilli sings a short passage from an opera aria by Verdi, once at the low tuning, then at the high tuning, and then once more at the low tuning again. During the demonstration, Cappuccilli points out that at the high tuning, he had to do things to shift his voice on the highest notes which Verdi didn’t intend, and which changed the color of the sound. The superiority of the low tuning was clear to all in attendance.

The success of the Schiller Institute’s campaign unleashed a total brawl in the U.S. and Europe, and the legislation that was introduced in Italy in 1988 was eventually defeated, upon intense pressure from the United States on the Italian government not to pass it. This should make people think: if music is just whatever pleases you, why would something like tuning be such an issue? Why would the oligarchy go to such efforts in 1815, and recently in 1988, to stop an effort to standardize the tuning pitch? What really is the issue here? The issue comes back to: What is man? What is the power of music for mankind? Is it arbitrary? Is it whatever you want it to be? What does that kind of opinion lead to? For an answer, look around society today! Look at the entertainment culture that this has led to, and to the political and economic crisis created within society, versus what would be possible if we had a culture which was dedicated to the truthfulness of this kind of music, of the kind of principles involved in developing and maintaining classical music in society.

That is the core of our political mission today. Reviving the best of our culture, as seen in the principles of great classical music, is something which the United States and Europe, in particular, can decide to give as our offering to the collaborative, harmonic process taking shape in the world today.